When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how does the FDA make sure that’s true? The answer lies in bioequivalence studies - the scientific backbone of every generic drug approval in the U.S.

What Bioequivalence Really Means

Bioequivalence isn’t about looking the same or tasting the same. It’s about proving that a generic drug delivers the same amount of active ingredient into your bloodstream at the same rate as the brand-name drug. The FDA defines it clearly: there must be no significant difference in how quickly and how much of the drug enters your system when both versions are taken under the same conditions.This isn’t just theory. It’s the law. Since the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act, generic manufacturers have been required to prove bioequivalence before their products can be sold. Without this proof, a generic drug can’t get FDA approval - no matter how cheap it is to make.

The Two Rules: Pharmaceutical and Bioequivalence

Before a generic drug even gets to bioequivalence testing, it must pass a simpler check: pharmaceutical equivalence. That means the generic must have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form (like tablet or capsule), and route of administration (like oral or injectable) as the original brand-name drug.But that’s not enough. Two pills can look identical and still behave differently in your body. One might dissolve too slowly. Another might be absorbed unevenly. That’s why bioequivalence is the real gatekeeper.

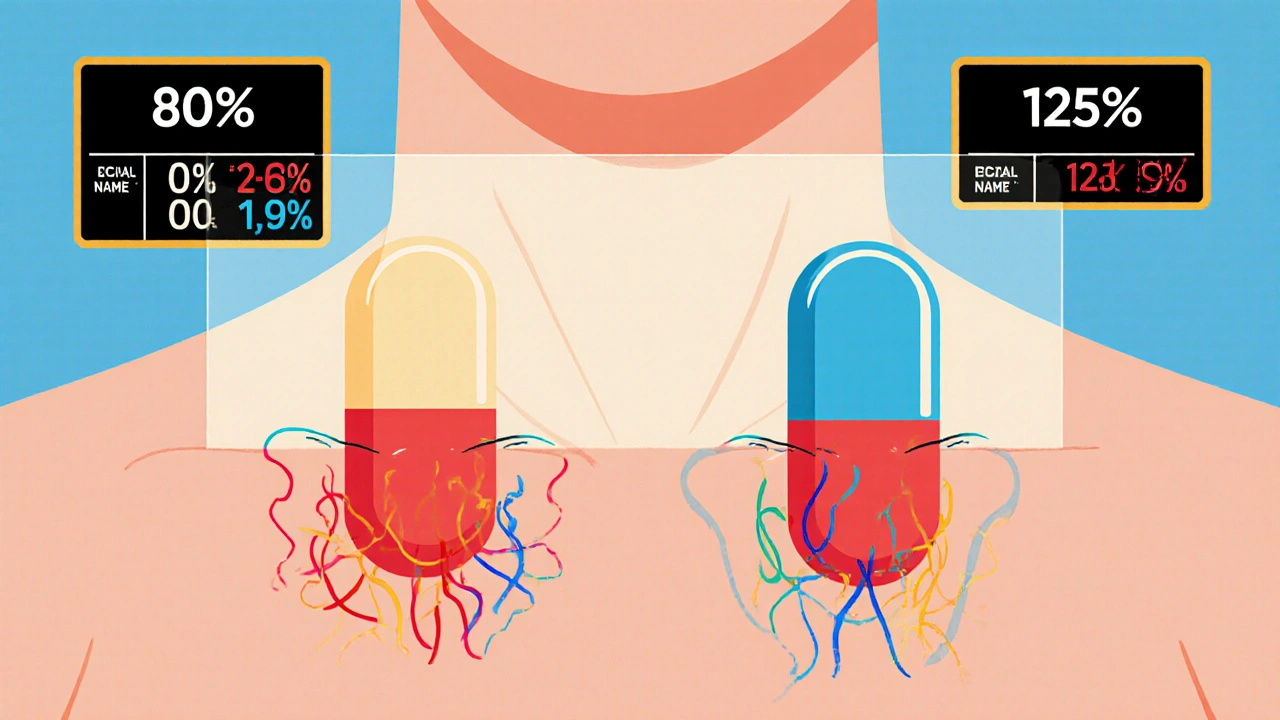

The 80/125 Rule: The Golden Standard

The FDA uses two key measurements to judge bioequivalence: AUC and Cmax.- AUC (Area Under the Curve) tells you how much of the drug gets absorbed over time - the total exposure.

- Cmax (Maximum Concentration) tells you how fast the drug reaches its peak level in your blood.

To pass, the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of the generic drug’s AUC and Cmax compared to the brand-name drug must fall between 80% and 125%. This is known as the 80/125 rule. It’s been the gold standard since 1992 and hasn’t changed.

Why those numbers? Because studies show that if the generic’s absorption is within this range, the clinical effect - how well it works and how safe it is - will be the same. If the generic delivers 85% of the drug’s exposure compared to the brand, it’s still considered equivalent. Same if it delivers 120%. But if it’s 75% or 130%? That’s a red flag.

Who Gets Tested? And How?

Bioequivalence studies are almost always done in healthy volunteers - usually between 24 and 36 people. They take the generic and the brand-name drug in separate sessions, often weeks apart, with a washout period in between. The study is usually done under fasting conditions because food can interfere with absorption.But not all drugs behave the same. If a drug’s absorption is affected by food - like some cholesterol or antibiotic meds - the FDA requires a second study done after a meal. That’s called a fed study. It’s extra work, but it’s necessary to make sure the drug works in real life, not just in a lab.

All studies must follow strict rules. Blood samples are taken at precise times. Labs must use validated methods to measure drug levels. Everything is documented under Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) standards. The FDA audits these studies. One mistake in sample handling or data recording can sink an entire application.

When Bioequivalence Studies Aren’t Needed

Not every generic drug needs a full human study. The FDA allows biowaivers for certain products where the risk of difference is extremely low.For example:

- Oral solutions with the same ingredients and concentrations as an approved brand - no study needed.

- Topical creams or ointments meant to work on the skin, not in the bloodstream - in vitro tests can replace human trials.

- Inhalers with identical ingredients and delivery mechanisms - if they match the reference product exactly, a biowaiver may apply.

These waivers follow the Q1-Q2-Q3 rule:

- Q1: Same active and inactive ingredients.

- Q2: Same dosage form and strength.

- Q3: Same physical and chemical properties - like pH, solubility, particle size.

If all three match, the FDA trusts the science. That saves manufacturers time and money - sometimes up to a year of development.

Special Cases: Narrow Therapeutic Index Drugs

Some drugs are like tightropes. Too little doesn’t work. Too much is dangerous. These are called Narrow Therapeutic Index (NTID) drugs. Examples include warfarin, levothyroxine, and phenytoin.For these, the FDA doesn’t use the standard 80/125 rule. Instead, it requires a tighter range: 90% to 111%. That’s because even small differences in absorption can lead to serious side effects - like blood clots or seizures.

Manufacturers of NTID generics must provide extra data. Sometimes that means more volunteers, longer study periods, or even clinical endpoint studies (measuring actual patient outcomes, not just blood levels). These are harder and more expensive to run - but they’re non-negotiable.

What Happens When Studies Fail?

The FDA approves only about 43% of generic drug applications on the first try. The rest get rejected or asked for more data. Why?- Wrong sample size - too few volunteers, not enough statistical power.

- Poor analytical methods - labs using outdated or unvalidated tests.

- Incorrect study design - not following the product-specific guidance.

- Incomplete documentation - missing protocols, raw data, or audit trails.

The biggest mistake? Ignoring the FDA’s Product-Specific Guidance (PSG). There are over 2,100 of these documents. Each one details exactly how to test a specific drug - from the number of volunteers to the type of blood test to use. Companies that follow the PSG have a 68% first-time approval rate. Those who don’t? Just 29%.

Costs and Time: The Real Price of Approval

Running a single bioequivalence study costs between $500,000 and $2 million. That’s why many generic manufacturers outsource to specialized contract research organizations (CROs).Even with the right study, the whole ANDA approval process takes 14 to 18 months on average. That’s down from 36 months in the 1990s - thanks to better guidelines and the FDA’s Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA). But delays still happen. Topical generics, for example, had a 78% failure rate in 2022 due to bioequivalence issues.

Now, the FDA is pushing for faster approvals for drugs made in the U.S. with U.S.-sourced ingredients through its Domestic Generic Drug Manufacturing Pilot Program. It’s not a guarantee, but it can shave months off the review clock.

The Future: Modeling, Complexity, and Global Alignment

The FDA is moving beyond traditional studies. For complex drugs - like inhalers, patches, or injectables - they’re using physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling. This computer simulation predicts how a drug behaves in the body based on its chemical properties, eliminating the need for human trials in some cases.International standards are also aligning. The FDA and Europe’s EMA now agree on 87% of bioequivalence requirements. That means a study approved in the U.S. is more likely to be accepted abroad - making global launches easier for manufacturers.

By 2024, the FDA plans to release draft guidance for 45 new complex product types. That includes topical products with systemic effects, nasal sprays, and drug-device combos like auto-injectors. These will need new testing strategies - and manufacturers who adapt will lead the market.

Why This Matters to You

You might think bioequivalence is just a bureaucratic hurdle. But it’s what keeps you safe. Every time you save money by choosing a generic, you’re relying on this system to work.It’s not perfect. Some experts argue the 80/125 rule is too broad for highly variable drugs. The FDA agrees - and has already created special rules for those cases. But overall, the system has delivered: 90% of U.S. prescriptions are filled with generics, and they cost only 23% of what brand-name drugs do.

That’s the power of science-backed regulation. It doesn’t just lower prices. It protects health. And that’s why the FDA’s bioequivalence requirements aren’t just paperwork - they’re a promise.

What is the 80/125 rule in bioequivalence studies?

The 80/125 rule is the FDA’s statistical standard for bioequivalence. It means the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of the generic drug’s AUC and Cmax compared to the brand-name drug must fall between 80% and 125%. If it does, the two drugs are considered bioequivalent and therapeutically interchangeable.

Do all generic drugs need human bioequivalence studies?

No. Some generics qualify for biowaivers - meaning no human study is needed. This applies to products like oral solutions, topical creams for local effect, and certain inhalers - as long as they match the reference drug exactly in ingredients, form, and physical properties (Q1-Q2-Q3 criteria).

Why are narrow therapeutic index drugs treated differently?

Narrow therapeutic index (NTID) drugs like warfarin and levothyroxine have a very small margin between effective and toxic doses. Even small differences in absorption can cause serious harm. So the FDA requires a tighter bioequivalence range of 90% to 111% instead of the standard 80% to 125%.

What happens if a bioequivalence study fails?

If a study fails, the FDA issues a complete response letter asking for more data or corrections. Common reasons include poor study design, inadequate sample size, or not following the product-specific guidance. About 57% of ANDA applications require at least one revision before approval.

How long does it take to get a generic drug approved?

The average time from ANDA submission to approval is 14 to 18 months. Bioequivalence studies are often the biggest bottleneck. Companies that follow the FDA’s product-specific guidances get approved about 3 months faster than those who don’t.

Can I trust generic drugs as much as brand-name ones?

Yes. The FDA requires generic drugs to meet the same quality, strength, purity, and stability standards as brand-name drugs. Bioequivalence studies ensure they work the same way in your body. Over 90% of U.S. prescriptions are filled with generics - and they’ve been safely used for decades.

Manufacturers who master the bioequivalence process don’t just get approval - they gain market access, lower costs, and public trust. For patients, it means affordable, reliable medicine. For the system, it’s a win-win - as long as the science stays sharp.

Gus Fosarolli

November 27, 2025 AT 17:00So let me get this straight - you’re telling me I can swap my $200 brand-name pill for a $5 generic and the FDA guarantees it won’t turn me into a human guinea pig? And the whole thing hinges on some 80/125 math magic? I’m not saying I trust it… but I’m definitely buying it. 😏

Evelyn Shaller-Auslander

November 28, 2025 AT 16:20this is so cool i never knew how much work went into generics. like… someone actually sits there with blood samples and timers?? wow. thanks for explaining 😊

Leigh Guerra-Paz

November 29, 2025 AT 21:32Oh my gosh, I just read this entire thing and I’m so impressed! I mean, the fact that they test under fasting AND fed conditions? And the Q1-Q2-Q3 rule? And the fact that they audit every single data point?! It’s not just about saving money - it’s about science, discipline, and patient safety. I’m literally teary-eyed right now. We need more of this level of rigor in healthcare. Thank you for sharing this!

Jordyn Holland

November 30, 2025 AT 14:38Wow. Just… wow. A 90% approval rate for generics? That’s like saying your cousin’s DIY homeopathy is just as good as Pfizer. The 80/125 rule? That’s not science - that’s a casino bet. And yet, somehow, we’re all supposed to trust this? I’m just glad I don’t need to take anything expensive anymore… because I’d rather die than risk my body on this.

Jasper Arboladura

December 1, 2025 AT 16:11The 80/125 rule is statistically arbitrary. Real bioequivalence requires Cmax and AUC variance analysis under multiple dosing regimens with pharmacodynamic endpoints - not just fasting PK in 24 college kids. The FDA’s approach is a compromise born of regulatory expediency, not scientific purity. Most clinicians don’t even understand the difference between bioavailability and bioequivalence. Pathetic.

Joanne Beriña

December 1, 2025 AT 22:11So now we’re letting foreign labs in India and China run our drug tests? And you call this ‘science’? Back in my day, we did bioequivalence studies in American labs with American volunteers - not some guy in Bangalore with a $200 spectrometer! This is why our healthcare is falling apart. America first - or at least, America-tested!

ABHISHEK NAHARIA

December 2, 2025 AT 05:11Interesting discourse on bioequivalence but one must question the epistemological foundations of pharmaceutical equivalence. The reductionist model of AUC and Cmax fails to account for gut microbiome variability, genetic polymorphisms in CYP450 enzymes, and inter-individual pharmacodynamic responses. Is bioequivalence merely a regulatory fiction? Or is it the last bastion of scientism in a post-truth world?

Hardik Malhan

December 3, 2025 AT 00:17Biowaivers under Q1-Q2-Q3 are legit when physicochemical properties align. PK modeling validates absence of dissolution limitations. FDA PSGs are non-negotiable - deviate and you’re in the rejection queue. CROs with validated LC-MS/MS methods are key. Study design must mirror reference product’s PK profile. No shortcuts.

Casey Nicole

December 3, 2025 AT 19:55Why do we even bother with all this? I mean, if it looks the same and costs less, who cares if the math says 85%? My cousin took generic Adderall and she’s fine. My mom takes generic levothyroxine and she’s alive. So why are we wasting millions on blood draws? The system is broken. We need to trust people, not spreadsheets.

Kelsey Worth

December 4, 2025 AT 12:30ok but like… if the 80/125 rule is so solid why do some people swear their generic Zoloft made them cry for three weeks? maybe the rule is fine for most… but for some of us? it’s a gamble. and i’m just tired of being the lab rat. 🤷♀️

shelly roche

December 4, 2025 AT 21:47I love how this post breaks it down so clearly - it’s not just about money, it’s about dignity. Everyone deserves safe, affordable medicine. Whether you’re in rural Ohio or outer Mumbai, this system? It’s the quiet hero. And the fact that the FDA’s working on PBPK modeling for complex drugs? That’s innovation with heart. Keep going, science. We’re rooting for you.

Nirmal Jaysval

December 5, 2025 AT 19:39Generic drugs are fine but why not make everything in India? We save money and create jobs there. America is too expensive for everything. Also why do we need 24 volunteers? One guy with a smartwatch and a urine test should be enough. Too much science is bad for business.