When your blood clots too easily, it can lead to dangerous blockages in your legs, lungs, or brain. But if it doesn’t clot enough, even a small cut can become life-threatening. Finding the right balance is the core challenge of anticoagulation therapy - and it’s not as simple as just taking a pill.

Why Blood Clots Matter in Heart Health

Clotting disorders aren’t just about veins. In heart health, the biggest risk comes from atrial fibrillation - an irregular heartbeat that lets blood pool in the heart’s upper chambers. That pooled blood can form clots, which may break loose and cause a stroke. About 1 in 3 people with atrial fibrillation will have a stroke if they don’t take a blood thinner. That’s why doctors recommend anticoagulants for patients with a CHA₂DS₂-VASc score of 2 or higher in men, or 3 or higher in women.

But it’s not just AFib. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) - blood clots in the legs or lungs - also need long-term anticoagulation. Even people with mechanical heart valves, which can trigger clotting, require constant protection. The goal? Prevent clots without causing dangerous bleeding.

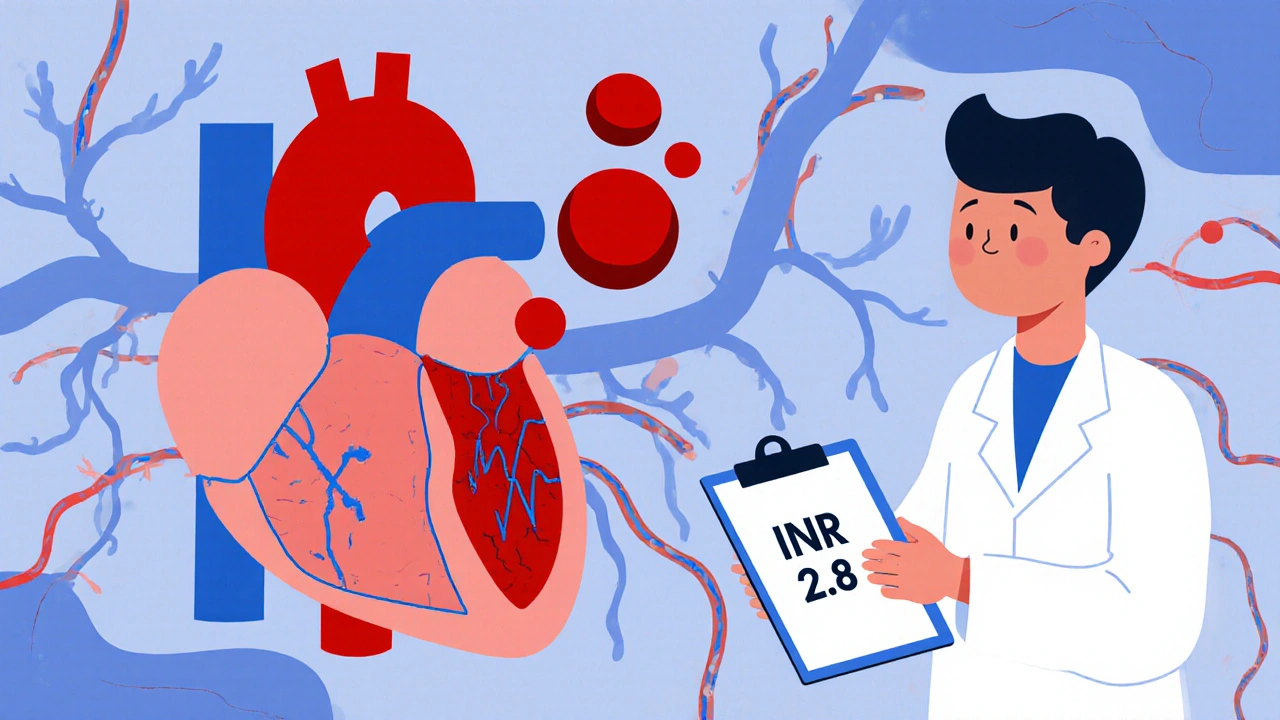

INR: The Old-School Tracker

For decades, warfarin was the only option. It works by blocking vitamin K, a key ingredient your body needs to make clotting factors. But here’s the catch: warfarin’s effect changes constantly. What works one week might be too weak or too strong the next.

That’s where INR - International Normalized Ratio - comes in. It’s a standardized number that tells your doctor how long your blood takes to clot. A normal INR is around 1.0. For most people on warfarin, the target is 2.0 to 3.0. For mechanical heart valves, it’s higher - 2.5 to 3.5.

Getting there isn’t easy. You need blood tests every week at first, then every 2 to 4 weeks once stable. Even then, your INR can swing because of what you eat (vitamin K-rich foods like kale or spinach), other medications, or even changes in your liver function. About 70% of patients on warfarin spend less than 70% of their time in the ideal range - meaning they’re either under- or over-protected most of the year.

And if your INR goes above 4.0? Your risk of major bleeding jumps 2.5 times. That’s why many patients dread warfarin - it’s effective, but it’s a constant tightrope walk.

DOACs: The New Generation

Between 2010 and 2015, a new group of drugs hit the market: direct oral anticoagulants, or DOACs. These include apixaban (Eliquis), rivaroxaban (Xarelto), dabigatran (Pradaxa), and edoxaban (Savaysa). They work differently than warfarin - some block factor Xa, others block thrombin. No vitamin K interference. No need to count greens.

They’re also faster. Warfarin takes days to build up in your system and days to clear out. DOACs work within hours and leave your body in a day or two. That means if you need surgery, you can stop them 24 to 48 hours before - not five days like with warfarin.

And they’re safer. The ARISTOTLE trial showed apixaban caused 31% fewer major bleeds than warfarin. Real-world data confirms it: DOACs lower overall bleeding risk by about 25-30% compared to warfarin. For most people with non-valvular atrial fibrillation, guidelines now say DOACs are the first choice.

The Trade-Offs: Convenience vs. Control

DOACs sound perfect - no blood tests, no diet changes, fewer bleeds. But they’re not without downsides.

First, you can’t easily check if they’re working. There’s no INR equivalent. Labs can test anti-Xa levels for some DOACs, but it’s not routine, and results vary by lab. If you’re bleeding or need emergency surgery, your doctor might not know how much drug is still in your system.

Second, reversal agents exist - but they’re expensive. Idarucizumab reverses dabigatran - but costs about $5,000 per vial. Andexanet alfa reverses apixaban and rivaroxaban - and costs $18,000 per dose. These are life-saving, but not always accessible.

Third, kidney function matters. DOACs are cleared through the kidneys. If your creatinine clearance drops below 15-30 mL/min (depending on the drug), they’re not safe. Warfarin doesn’t care about your kidneys - it’s metabolized by the liver.

And then there’s cost. Warfarin costs $4 to $30 a month. DOACs? $350 to $550. Even with insurance, copays can hit $400+. A 2023 JAMA study found 28% of Medicare patients quit DOACs within a year because they couldn’t afford them.

Who Still Needs Warfarin?

DOACs are great - but not for everyone.

If you have a mechanical heart valve, warfarin is your only option. DOACs don’t work well here. Same goes for moderate-to-severe mitral stenosis. In these cases, the risk of clotting is too high, and DOACs haven’t been proven safe.

People with cancer-related clots also face special rules. For gastrointestinal or genitourinary cancers, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) is still preferred over DOACs. Why? DOACs increase bleeding risk by 55% in these patients, according to the Hokusai VTE Cancer trial.

And if you’re on dialysis? Warfarin is often the only choice. DOACs are not approved for severe kidney failure.

Bleeding Risks and What to Watch For

All anticoagulants increase bleeding risk. Bruising? Common. Nosebleeds? Normal. But if you’re bleeding for more than 10 minutes, vomiting blood, coughing up blood, or having a sudden severe headache - get help immediately.

Some DOACs carry higher GI bleeding risks. Rivaroxaban and dabigatran are linked to more stomach bleeding than apixaban. In one survey, 41% of users reported gastrointestinal issues with rivaroxaban. Apixaban users reported fewer of these problems.

And don’t forget spinal procedures. If you’re getting an epidural or spinal tap while on a DOAC, you risk a spinal hematoma - a rare but devastating complication. Guidelines say to stop DOACs at least 24 hours before, and longer if you have kidney issues.

How Long Should You Stay on Blood Thinners?

There’s no one-size-fits-all answer. For a first blood clot caused by surgery or trauma, 3 months is usually enough. If the clot happened for no clear reason - an unprovoked DVT or PE - you might need lifelong therapy.

Doctors use tools like the HAS-BLED score to weigh bleeding risk. If your score is below 3 and you have no history of bleeding, indefinite anticoagulation is often recommended. If your score is high, you might try stopping after 6 to 12 months - but only under close supervision.

And here’s the thing: even if you feel fine, stopping too soon can bring back clots. One patient on Reddit shared, “I stopped my pill after 6 months because I felt fine. Two weeks later, I had a PE.”

What’s Next? The Future of Anticoagulation

Science is moving fast. In November 2023, the FDA approved milvexian - a new drug that blocks factor XIa. Early trials show it prevents clots just as well as apixaban, but with 22% less bleeding. That’s huge.

Other candidates are in the works: RNA-based drugs like fitusiran that reduce antithrombin production, and AI tools that predict your bleeding risk with 82% accuracy based on your genes, lifestyle, and lab values.

For now, though, the choice comes down to you: Do you want less monitoring and more cost? Or more control and less expense? Your doctor will help you weigh the risks - but the final decision is yours.

Real-Life Choices

Juliet, a nurse who ignored her own DVT symptoms while caring for her child, eventually started apixaban. She says, “I didn’t want weekly blood draws. I didn’t want to worry about my broccoli. Apixaban gave me back my life.”

On the other hand, Robert, 71, stayed on warfarin because his copay is $18 a month. “I’ve been on it for 12 years. I know my numbers. I don’t want to risk a $500 pill that might not be covered next year.”

Both are right. There’s no perfect drug - just the right one for your life.

What does INR stand for, and why is it important?

INR stands for International Normalized Ratio. It’s a standardized measure of how long your blood takes to clot. For people on warfarin, keeping INR between 2.0 and 3.0 ensures the drug is working well enough to prevent clots without causing dangerous bleeding. If your INR is too low, you’re at risk for stroke or clotting. If it’s too high - especially above 4.0 - your risk of internal bleeding skyrockets.

Are DOACs safer than warfarin?

Yes, for most people. DOACs reduce the risk of major bleeding by 25-31% compared to warfarin, especially brain bleeds. Apixaban has the lowest bleeding risk among DOACs. However, some DOACs like rivaroxaban and dabigatran carry a higher risk of stomach bleeding. They’re also not safe for people with mechanical heart valves or severe kidney disease. So while DOACs are safer overall, they’re not safe for everyone.

Can I stop taking my blood thinner if I feel fine?

No. Feeling fine doesn’t mean you’re not at risk. Many people who stop anticoagulants too soon have another clot - sometimes within days. If you had an unprovoked blood clot (no surgery or injury), guidelines recommend lifelong therapy unless your bleeding risk is very high. Always talk to your doctor before stopping - never decide on your own.

What should I do if I miss a dose of a DOAC?

If you miss a dose of a DOAC, take it as soon as you remember - but only if it’s within 6 hours of your usual time. If it’s been longer, skip the missed dose and take your next one at the regular time. Never double up. Missing doses increases your clotting risk, especially with drugs like rivaroxaban that have short half-lives. Set phone reminders if you need to.

Do I need to avoid certain foods or alcohol on DOACs?

Unlike warfarin, DOACs don’t interact with vitamin K-rich foods like spinach, kale, or broccoli. You don’t need to restrict them. But heavy alcohol use (more than 3 drinks a day) can increase bleeding risk with any anticoagulant. Also, avoid herbal supplements like garlic, ginkgo, or St. John’s wort - they can interfere with DOACs. Always check with your doctor before starting any new supplement.

How often should I get my kidneys checked on DOACs?

You should have your kidney function checked at least once a year, and every 6 months if you’re over 75, have diabetes, or already have reduced kidney function. DOACs are cleared by the kidneys, and if your creatinine clearance drops below 15-30 mL/min (depending on the drug), they become unsafe. Your doctor will use blood tests to measure your creatinine and calculate your estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).

Josh Gonzales

November 26, 2025 AT 03:02Just want to say DOACs are a game changer for people who can afford them. No more weekly blood draws, no more worrying if your kale salad ruined your INR. I’ve been on apixaban for 5 years and honestly? I forgot I was on a blood thinner until I saw the prescription bottle. Life’s too short to count greens.

katia dagenais

November 27, 2025 AT 04:00Let’s be real - this whole anticoagulation industry is a money machine. Warfarin’s been around since WWII and somehow we’re still pretending DOACs are some miracle breakthrough. Meanwhile, the average person can’t even get their $400 copay covered and doctors act like it’s a personal choice. It’s not about safety - it’s about who gets to live and who gets priced out.

Josh Zubkoff

November 27, 2025 AT 22:49Apixaban users report fewer GI issues? That’s hilarious. My cousin took it for 8 months and ended up in the ER with a bleeding ulcer. The drug reps told her it was ‘unlikely’ - yeah, right. And now she’s on warfarin because her insurance won’t cover the reversal agent. This isn’t medicine, it’s a lottery.

Valérie Siébert

November 28, 2025 AT 14:24Y’all are overcomplicating this. You want less monitoring? Take DOACs. You want to save money? Stick with warfarin. You want to live? Don’t stop taking it. End of story. Stop reading Reddit like it’s a medical journal and start listening to your doc. Also - yes, you still need to check your kidneys. No, your 70-year-old body doesn’t magically heal itself just because you feel ‘fine’.

Emily Craig

November 30, 2025 AT 07:32I was on warfarin for 3 years after my PE. Weekly pokes. Broccoli guilt. Constant anxiety. Then I switched to apixaban - and for the first time in years, I slept through the night. I’m not saying it’s perfect, but it gave me back my peace. To anyone scared of the cost - talk to your pharmacist. There are patient assistance programs. You’re not alone.

Jacqueline Aslet

November 30, 2025 AT 11:24It is, however, a matter of profound ethical concern that the pharmaceutical industry has engineered a system wherein life-sustaining medication is rendered inaccessible to a significant proportion of the population on the basis of socioeconomic status. One must question whether the clinical superiority of DOACs justifies the systemic inequity they perpetuate.

Jack Riley

November 30, 2025 AT 15:32INR is a relic. Like fax machines or dial-up. We measure blood pressure without pulling out a stethoscope and a mercury column - why are we still poking fingers for INR? DOACs aren’t perfect, but they’re the future. And yes, the reversal agents cost more than a used car - but so does a stroke. Someone’s gotta pay. Might as well be the insurance companies.

Also, if you think your kidney function is fine because you don’t feel sick - you’re wrong. Kidneys don’t scream until they’re already dead. Get the labs. Do it. Now.

And for the love of god, stop Googling ‘DOACs cause cancer’ and believe your doctor. No, they don’t. That’s a Reddit myth from 2017.

Ellen Sales

November 30, 2025 AT 15:50My dad’s on warfarin. He’s 82. He eats kale every day. He checks his INR every 3 weeks. He’s been stable for 10 years. He doesn’t want to switch because he knows his numbers. He’s not afraid of the needle - he’s afraid of being treated like a statistic. We owe people like him respect, not condescension.

Also - if you’re on DOACs and you’re skipping doses because you’re ‘busy’ - you’re playing Russian roulette. That’s not bravery. That’s negligence.

Erika Hunt

December 2, 2025 AT 05:59I think the real issue here isn’t warfarin vs DOACs - it’s that we’ve turned healthcare into a product lineup. People aren’t patients, they’re consumers. And when you treat medicine like a subscription service, you lose the human part. Juliet and Robert? They’re not ‘choices’ - they’re survivors adapting to a broken system. We need to fix the system, not just the pills.

Roscoe Howard

December 2, 2025 AT 22:24DOACs are a foreign innovation. In America, we built the best healthcare system in the world - and now we’re letting Europeans and Canadians dictate our treatment protocols? Warfarin has been tested on millions. DOACs? Five-year trials. That’s not science - that’s corporate greed wrapped in a lab coat.

Rachel Villegas

December 4, 2025 AT 19:24Just wanted to say thank you for writing this. My mom had a stroke last year because she stopped her blood thinner after 6 months because she ‘felt fine.’ She’s okay now, but she’ll never walk the same. Please don’t stop. Ever. Even if you think you’re fine. You’re not.

Caroline Marchetta

December 5, 2025 AT 04:03Oh wow. Another glowing article about DOACs. Let’s ignore the 28% of Medicare patients who quit because they can’t afford them. Let’s ignore the fact that reversal agents cost more than a month’s rent. Let’s ignore that 70% of warfarin patients are out of range most of the year - but hey, at least they’re ‘in control.’

Meanwhile, my sister’s on apixaban. She’s 32. She has no insurance. She takes it every other day. She says she’s ‘fine.’ I cry every time she says that.

Karen Willie

December 5, 2025 AT 21:05If you’re on DOACs and you’re worried about bleeding - that’s normal. But don’t let fear paralyze you. Talk to your doctor. Get your labs. Know your numbers. And if you’re struggling with cost? Ask about generics. Ask about coupons. Ask your pharmacist. You’d be surprised how many options exist. You’re not alone in this.

Andrew McAfee

December 7, 2025 AT 07:49Man I’m from Texas and we don’t do this fancy stuff. My cousin’s on warfarin. He eats steak, he drinks beer, he checks his INR once a month. He’s alive. He’s happy. You don’t need a PhD to take a pill. Just don’t stop.

Josh Gonzales

December 8, 2025 AT 20:11Missed a dose? Skip it. Don’t double up. That’s the rule. And if you’re on rivaroxaban and you’re having stomach pain - stop. Don’t wait. Go to the ER. I’ve seen too many people wait because they ‘don’t want to bother anyone.’ You’re not bothering anyone. You’re saving your life.