The European Union’s generic drug market is under major change. In 2025, new rules are reshaping how generic medicines reach patients across 27 countries. These aren’t small tweaks-they’re structural shifts that affect pricing, timing, and who can enter the market. If you’re a manufacturer, pharmacist, or just someone who relies on affordable meds, you need to understand what’s happening.

How Generic Drugs Get Approved in the EU

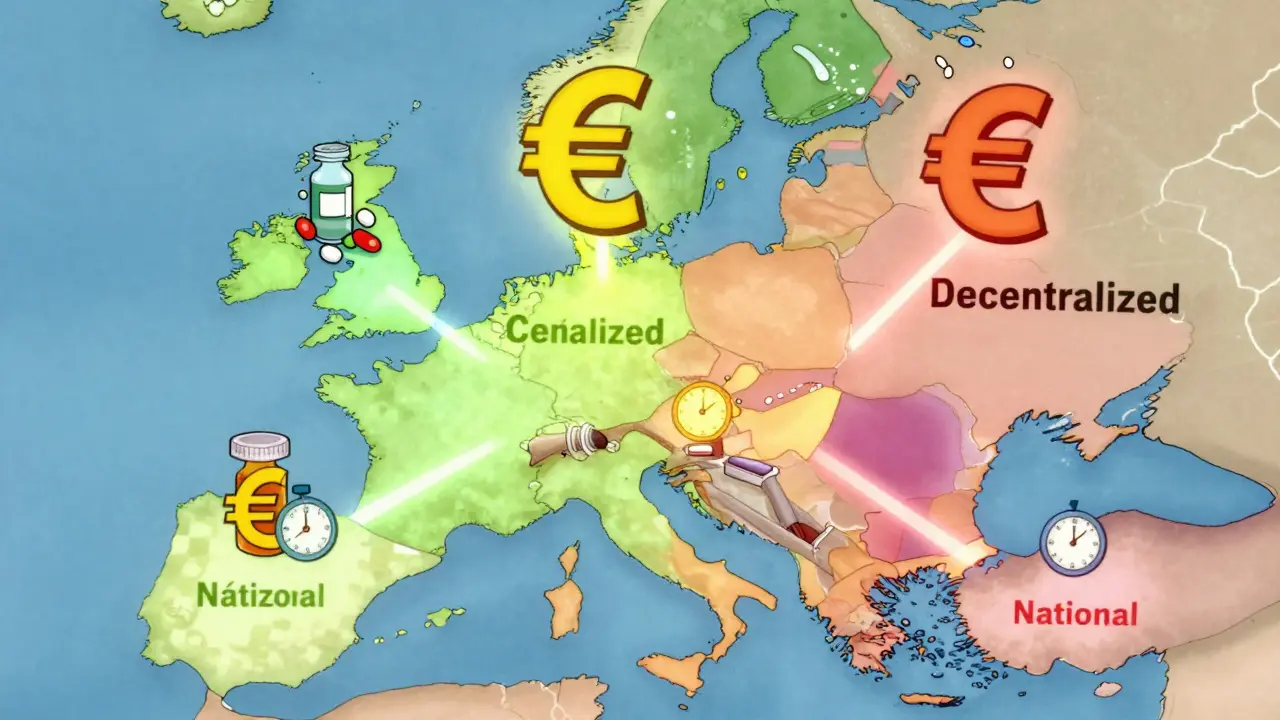

There’s no single path to get a generic drug approved in Europe. Instead, there are four different systems, and each one changes how fast, how cheaply, and how widely a drug can be sold.

The Centralized Procedure is the fastest way to get EU-wide approval. You submit one application to the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and if approved, your drug can be sold in all 27 EU countries plus Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway. But it’s expensive-application fees alone cost around €425,000, and you’ll likely spend another €1.2 to €1.8 million on consultants and studies. Only big players with high-volume products-think drugs expected to sell over €250 million across the EU-can justify this route. Sandoz used this path for its version of Cosentyx and launched across Europe in Q2 2025, 11 months faster than the old methods allowed.

The Mutual Recognition Procedure (MRP) is the most popular. About 42% of generic applications use it. A company gets approval in one country first-the Reference Member State-then asks others to accept it. Sounds simple, right? Not really. Each country can still raise objections. Teva’s generic rosuvastatin got approved in Germany in early 2023, but pricing talks there delayed its launch in the Netherlands and Belgium by over eight months. The average time for MRP approval? 132.7 days, even though the official clock says 90.

The Decentralized Procedure (DCP) lets companies apply to multiple countries at once. No prior approval needed. But this is where things get messy. In 37% of cases, delays hit six months or more. Why? Because countries like Poland, Romania, or Bulgaria interpret quality rules differently than Germany or France. One company’s stability data might be fine in Paris but rejected in Warsaw. The process averages 247 days-way longer than the 210-day target.

The National Procedure is the slowest and most limited. Only 5% of applications use it. You apply to one country only. It takes 180 to 240 days. It’s only worth it if you’re targeting a single high-reimbursement market, like France or Italy. But even then, it’s often slower than MRP for multi-country launches.

What Every Generic Must Prove

No matter which route you take, you must prove your drug is identical to the original. Not just close-identical.

You need the same active ingredients, in the same amounts, in the same form-tablet, injection, inhaler, you name it. And you must prove it works the same way in the body. That’s done through bioequivalence studies. The EMA requires that the test drug’s absorption rate (Cmax) and total exposure (AUC) fall within 80% to 125% of the original drug’s numbers, with 90% confidence. No wiggle room.

But here’s where it gets complicated. Some countries demand extra tests. Germany’s BfArM requires additional pharmacodynamic studies for inhalers. France’s ANSM wants pediatric formulation details even if the original drug wasn’t tested on kids. These aren’t EU-wide rules-they’re national add-ons. A 2025 survey of 47 generic companies found that 68% listed inconsistent national requirements as their biggest headache.

The 2025 Pharma Package: Big Changes Coming

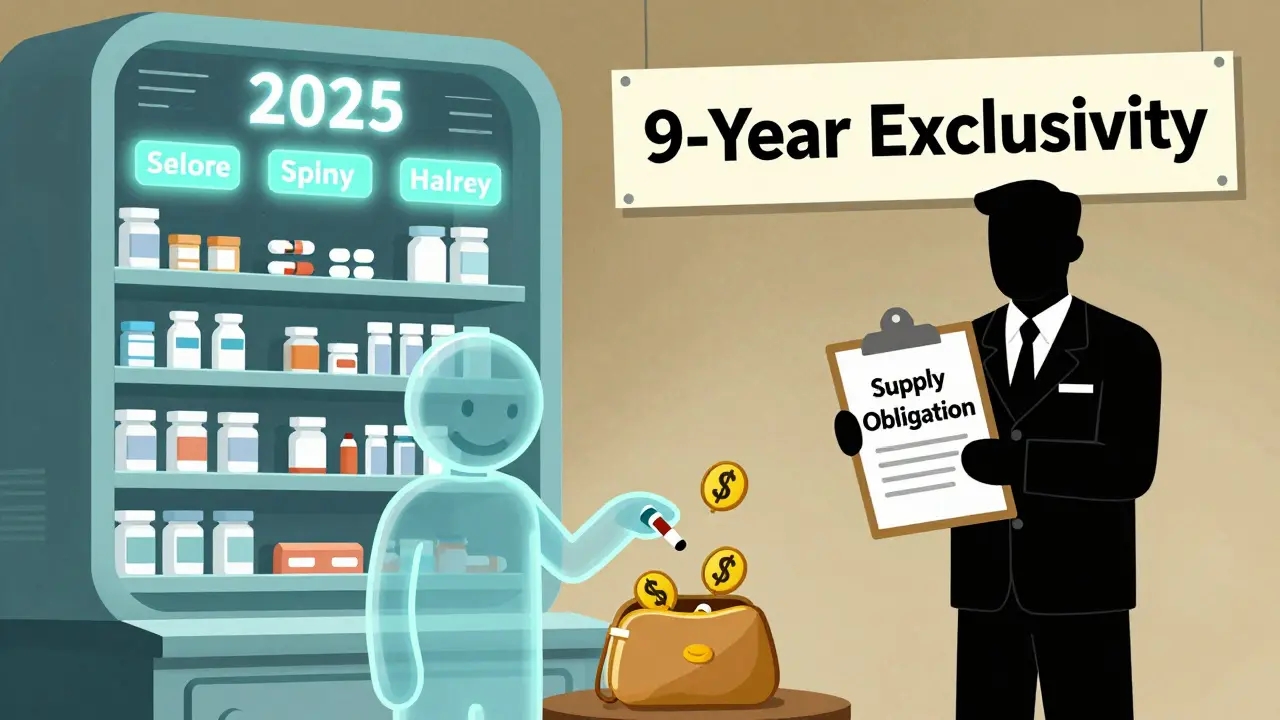

The biggest shift in two decades kicked in on June 4, 2025. The EU Pharma Package overhauled how generics enter the market.

First, data protection is shrinking. Before, a brand-name drug had 10 years of market exclusivity (8 years data protection + 2 years market protection). Now it’s 9 years total (8+1). You can stretch it to 10 years if your drug meets public health goals-like treating rare diseases or reducing hospitalizations. But that’s rare. Most generics will now face competition sooner.

Second, the Bolar exemption got a major boost. Before, generic makers could start negotiating prices and reimbursement just two months before the patent expired. Now, they can start six months early. This is huge. REMAP Consulting estimates this will cut average launch delays by 4.3 months. It also gives payers more power. Hospitals and insurers can now compare prices and demand discounts before the generic even hits shelves. That could lower launch prices by 12-18%.

Third, the obligation to supply rule now forces companies to keep enough stock to meet demand. If a generic drug disappears from shelves, regulators can fine the maker or even force them to license production to another company. This is meant to stop shortages-but it’s being implemented unevenly. Some countries define "sufficient quantities" loosely. Others are strict. Professor Panos Kanavos from LSE Health warns this patchwork could create artificial shortages in smaller markets.

Who’s Winning and Who’s Struggling

The EU generics market was worth €42.7 billion in 2024. Growth is strongest in Central and Eastern Europe-9.8% annually. But who’s making the money?

Indian companies are rising fast. They got 38% of all EU generic approvals in 2024, up from 29% in 2020. Their low-cost manufacturing and aggressive pricing make them hard to beat on simple generics.

European firms like Sandoz and Viatris still hold 52% of the market. But they’re not winning on price. They’re winning on strategy. They use the Centralized Procedure for high-value drugs. They invest in complex formulations-inhaled steroids, injectables, long-acting tablets-that are harder for Indian firms to copy. And they’re adapting to the new rules faster.

Smaller European generics companies are caught in the middle. The new €490 million sales threshold for "Transferable Exclusivity Vouchers"-a bonus incentive for hitting market targets-puts them at a disadvantage. They can’t afford the upfront costs to compete with giants. Many are shifting focus to niche markets or partnering with Indian firms to share costs.

What Manufacturers Need to Do Now

If you’re making generics for Europe, you’re facing a new reality.

First, plan ahead. The EMA now recommends 15-18 months of prep time for Centralized Procedure applications. Six to eight months of that is just for bioequivalence studies-updated to meet the 2025 guidelines.

Second, budget for tech. By 2026, you must submit all product information in XML format (ePI). That means upgrading your IT systems. White & Case estimates this costs €180,000-250,000 per company. No one’s exempt.

Third, understand national quirks. Don’t assume the EMA’s rules are the whole story. Germany wants extra stability data for polymorphic compounds. France needs pediatric documentation. Spain has stricter impurity limits for older reference drugs. You need local legal and regulatory teams in each market you target.

And don’t rely on EMA’s free Q&A portal. A 2025 survey found 58% of companies got conflicting answers from national authorities compared to EMA guidance. You’re better off hiring local consultants.

What This Means for Patients

Here’s the bottom line: patients will get more affordable drugs faster. The EU expects generic prescriptions to rise from 65% to 69.2% by 2028. That’s over 100 million more prescriptions filled with generics each year.

But it’s not all good news. Some complex drugs-like biosimilars for rare conditions-might see slower entry. The 1-year default market protection could make companies think twice about investing in hard-to-copy products. And if supply rules are enforced unevenly, patients in smaller countries could still face shortages.

The real winners? Payers-hospitals, insurers, national health systems. They’ll have more leverage to negotiate lower prices before launch. The real losers? Companies that keep doing things the old way. The era of slow, fragmented approvals is ending.

What’s Next

The next big change hits on July 1, 2026: the revised data protection rules fully kick in. That’s when 78 high-value biologics currently in development will start facing generic competition sooner than expected.

The Critical Medicines Act, passed in March 2025, adds another layer. It requires stockpiling of 200 essential generics. That sounds good-until you realize it adds new quality checks and verification steps. For small manufacturers, that’s another barrier.

And then there’s the US-EU Framework Agreement, effective September 1, 2025. It adjusts tariffs on some pharmaceutical ingredients. No one knows yet if it will lower costs or raise them. But it’s another variable in a system already under pressure.

One thing is clear: the EU’s generic market is no longer a patchwork of national rules. It’s becoming a single, complex, high-stakes game. The rules are changing. The players are shifting. And the clock is ticking.

Kent Peterson

December 15, 2025 AT 14:24This is all just EU bureaucracy dressed up as progress-another layer of red tape to make cheap medicine harder to get. Why can’t they just standardize the damn rules? We don’t need 4 procedures, we need ONE. And now they want us to submit XML files? Seriously? I’m paying more for my pills because of paperwork.

Evelyn Vélez Mejía

December 15, 2025 AT 15:01What we are witnessing here is not merely regulatory evolution-it is the quiet dismantling of pharmaceutical feudalism. The erosion of data exclusivity, the empowerment of payers, the institutionalization of the Bolar exemption-these are not policy adjustments; they are ontological shifts in the relationship between health, capital, and sovereignty. The patient, once a passive recipient, is now an active agent in a market reconfigured by temporal foresight and economic realism. The old guard clings to margins; the new paradigm demands transparency. And oh-the irony of German pharmacodynamic studies for inhalers while Poland rejects stability data. It is not inefficiency-it is epistemic pluralism. We must not mistake complexity for chaos.

CAROL MUTISO

December 15, 2025 AT 16:42Wow, I didn’t realize how many hidden traps there were in this system. Like, Germany asking for extra studies on inhalers? That’s wild. And the fact that France wants pediatric details even when the original drug wasn’t tested on kids? That’s not ‘safety’-that’s overreach wrapped in a lab coat. But hey, at least the Bolar exemption is a win. Six months early to negotiate prices? That’s like giving patients a head start in a race they’ve been losing for decades. Small victories, right?

Patrick A. Ck. Trip

December 16, 2025 AT 23:01It’s encouraging to see the EU finally moving toward more predictable timelines. I know it’s complicated, but the fact that companies are now forced to maintain supply? That’s huge. I’ve had prescriptions disappear before-especially in rural areas. It’s not perfect, but it’s a step. And I’m glad Indian manufacturers are stepping up. More competition = better prices. Just hope the small EU firms don’t get crushed in the process.

amanda s

December 18, 2025 AT 16:36THEY’RE ALL IN ON THIS! THE EU, THE PHARMA GIANTS, THE INDIAN COMPANIES-THEY’RE ALL WORKING TOGETHER TO MAKE YOU PAY MORE WHILE TELLING YOU IT’S CHEAPER! THEY’RE USING ‘TRANSPARENCY’ AS A COVER FOR PRICE FIXING! AND DON’T EVEN GET ME STARTED ON THE XML THING-THAT’S A BACKDOOR FOR THE BIGGIES TO LOCK OUT SMALL COMPANIES! THIS IS A SCAM!

Michael Whitaker

December 19, 2025 AT 11:04One must acknowledge the elegance of the EU’s regulatory architecture-even as it is, admittedly, a labyrinthine monument to institutional inertia. The decentralized procedure, while inefficient, is a testament to the sovereignty of member states. One wonders, however, whether the 2025 reforms have merely replaced national fragmentation with centralized overreach. The Bolar exemption, though laudable, merely accelerates commodification. The patient remains an afterthought in a calculus of margins and market share.

Jigar shah

December 20, 2025 AT 21:07Interesting read. I’m from India, and we’ve been supplying generics to Europe for years. The 38% approval rate makes sense-our labs are efficient and costs are low. But the national add-ons? Yeah, that’s brutal. One country wants extra stability data, another wants pediatric info for a drug never meant for kids. It’s like playing 27 different video games with different rules. I’d love to know how many companies just give up and walk away.

Nishant Desae

December 21, 2025 AT 12:38Man, I’ve been in this industry for 15 years, and I’ve never seen a shift this big. I remember when we’d just submit one dossier and wait six months. Now it’s like climbing Mount Everest with a backpack full of bricks. But honestly? I’m hopeful. The fact that payers can start negotiating six months early? That’s a game-changer. It means real savings for hospitals, for families, for people who choose between medicine and groceries. And yeah, the XML thing is a pain-but it’s the future. We’ve got to adapt. Small companies? Partner up. Team up with Indian firms. Share the burden. We’re all in this together. The system’s broken? Fix it. Don’t quit.

Radhika M

December 22, 2025 AT 20:41So basically: if you’re a small company, forget the centralized route. It’s too expensive. Stick to one country, or team up with someone who can handle the paperwork. And don’t skip the local consultants-EMA’s answers are useless. Save your money on fancy labs, spend it on lawyers who know what each country really wants.

Philippa Skiadopoulou

December 24, 2025 AT 11:38Efficiency gains from the Bolar exemption are substantial. The 4.3-month reduction in launch delays is empirically validated. However, the uneven implementation of supply obligations risks market distortion. The Critical Medicines Act’s stockpiling requirement, while well-intentioned, introduces new compliance burdens disproportionate to small manufacturers. Regulatory harmonization remains aspirational.

Pawan Chaudhary

December 26, 2025 AT 04:32Hey, just wanted to say props to the EU for trying. I know it’s messy, but at least they’re trying to fix the system. My cousin in Poland got her meds delayed for months last year. If this helps even a little, it’s worth it. Keep pushing, guys. We’re all rooting for affordable meds.

Jonathan Morris

December 28, 2025 AT 01:14Let me guess-this whole ‘Pharma Package’ was written by lobbyists from Big Pharma. They knew the 1-year market protection would scare off biosimilar makers, and the XML requirement? That’s a $250k barrier to entry-designed to kill small competitors. And the ‘obligation to supply’? That’s a Trojan horse. They’ll use it to force licensing deals with their own subsidiaries. This isn’t reform-it’s consolidation disguised as progress.

Anna Giakoumakatou

December 28, 2025 AT 17:57How quaint. We’ve turned medicine into a spreadsheet. ‘Bioequivalence within 80–125%’-as if a pill’s soul can be quantified in AUC curves. And now we’re all supposed to be thrilled that patients will get ‘more affordable drugs faster’? As if affordability is the only metric that matters. What about dignity? What about the quiet, invisible labor of the pharmacist who explains to an elderly woman why her new generic tastes like chalk? The EU didn’t fix the system-they just made it faster at turning human need into a line item.