Pediatric Medication Safety Calculator

Calculate safe medication dosages for children based on weight and concentration. Never guess or estimate doses for children - small errors can be dangerous.

Important Safety Notes

Warning: This calculator is for educational purposes only. Always consult your healthcare provider before administering medication to children. Pediatric dosages are extremely sensitive - even small errors can be dangerous.

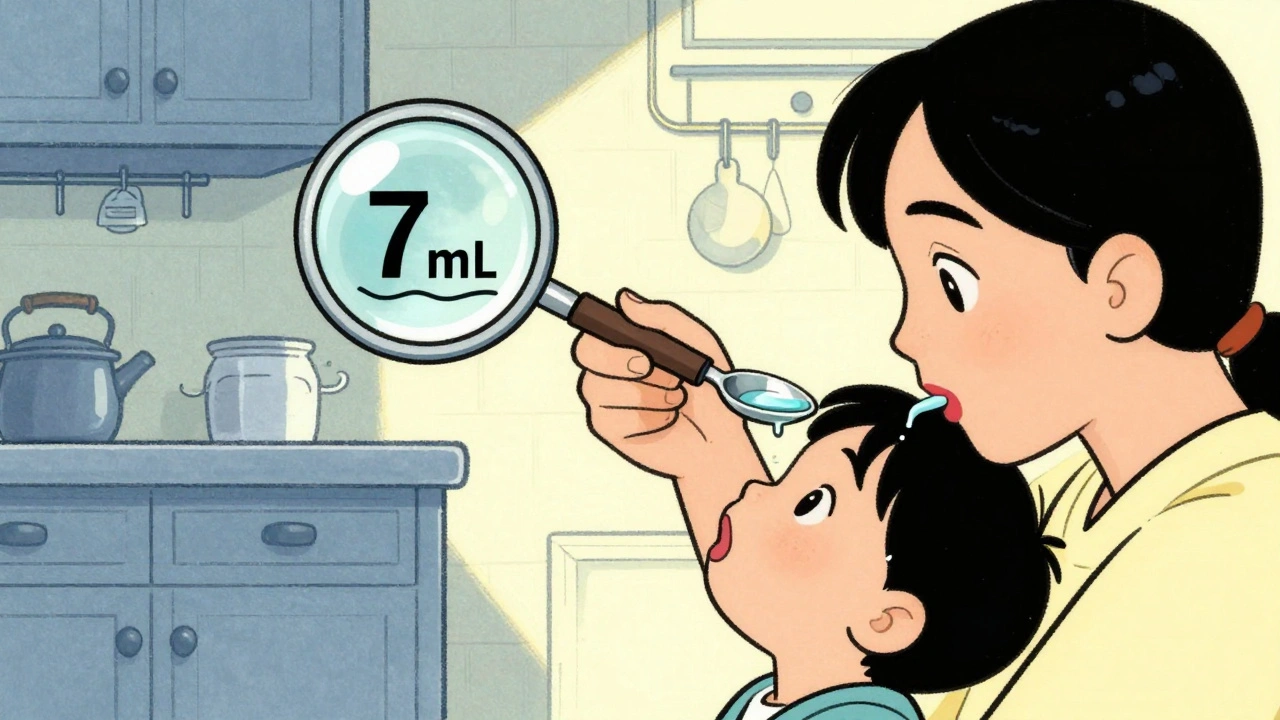

- Always use milliliter-only dosing devices (oral syringes or measuring cups marked in mL)

- Never use kitchen spoons for medication measurement

- Store medicine in child-resistant containers in a locked cabinet

- Never call medicine "candy" to children

Every year, 50,000 children under age 5 end up in emergency rooms because they got into medicine they shouldn’t have. Many of these cases aren’t accidents-they’re preventable mistakes. Parents think they’re being careful. They leave a bottle on the nightstand. They crush pills into applesauce. They say, "This is candy," to get their toddler to take it. But for kids, even a tiny dose of adult medicine can be deadly. Pediatric medication safety isn’t just about giving the right amount-it’s about understanding how children’s bodies work differently, how errors happen, and how to stop them before they do harm.

Why Kids Are More Vulnerable to Medication Errors

Children aren’t small adults. Their bodies process medicine in ways that change dramatically as they grow. A newborn weighing 3 kilograms and a 12-year-old weighing 40 kilograms might both need the same drug, but the difference in dosage isn’t linear-it’s exponential. One wrong decimal point can turn a safe dose into a lethal one.

Infants and young children have underdeveloped livers and kidneys. These organs are responsible for breaking down and flushing out drugs. In adults, this happens smoothly. In babies, it’s slow and unpredictable. That means a medicine that clears from an adult’s system in six hours might stay in a 6-month-old’s body for 18 hours or more. This isn’t theoretical-it’s why the Pediatrics journal warned in 2018 that children’s developing systems make them less able to tolerate even small medication errors.

And then there’s communication. A toddler can’t say, "My stomach hurts," or "I feel dizzy." They cry. They vomit. They go limp. By the time a parent notices something’s wrong, it might already be too late. That’s why prevention has to happen before the medicine even leaves the bottle.

The Most Common Mistakes That Put Kids at Risk

Medication errors in children aren’t random. They follow patterns. And most of them come down to three things: measuring wrong, storing wrong, and assuming wrong.

First, measuring. Giving 1 teaspoon of medicine when you meant 1 milliliter? That’s a fivefold overdose. One tablespoon instead of one teaspoon? That’s a threefold overdose. These aren’t hypotheticals-they’re real, documented errors that send kids to the ER. The problem? Most households still use kitchen spoons. They’re not precise. A teaspoon from your kitchen might hold 4 mL or 7 mL. That’s a 75% variation. No wonder the American Academy of Pediatrics now insists: only use milliliter-only dosing devices-oral syringes or measuring cups marked in mL, never teaspoons or tablespoons.

Second, storage. The CDC says 60% of poisonings happen because medicine was left within reach. Parents think a cabinet above the sink is safe. They’re wrong. Toddlers climb. They pull chairs. They open cabinets. And if the cap isn’t fully locked? A child can open a child-resistant bottle in under 30 seconds. That’s not a myth-it’s from a 2013 study in the Journal of Pediatrics. Even things you don’t think of as medicine-diaper rash cream, eye drops, prenatal vitamins-can be deadly in small amounts. They account for 20% of poisonings reported to poison control.

Third, assumptions. Many parents give OTC cough and cold medicine to kids under 6, even though it’s not recommended. Some crush pills because their child won’t swallow them. Others mix medicine into juice, hoping the flavor hides it. But if the child doesn’t finish the glass? They get an incomplete dose. And if they do? They might get too much. Worse, telling a child medicine is candy? That’s a direct path to accidental ingestion. Poison Control data shows it contributes to 15% of cases.

What Hospitals Are Doing to Keep Kids Safe

In hospitals, pediatric medication safety has become a science. The American Academy of Pediatrics laid out 15 evidence-based practices in 2018. Hospitals that follow them see error rates drop by 85%.

One key rule: use kilograms only. No more pounds. No more conversions. Weight is entered in kg. Dosing is calculated in mg/kg. Electronic systems block doses that exceed safe upper limits. This alone has cut weight-based errors-the leading cause of serious incidents-by more than half.

High-risk medications like opioids, insulin, or sedatives require a two-person check. One nurse prepares it. A second nurse verifies the dose, the weight, the route, and the time. No exceptions. This isn’t bureaucracy-it’s a safety net. A 2019 study in the American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy found hospitals with fewer than 100 pediatric patients annually had 3.2 times more errors than dedicated children’s hospitals. Why? Because general staff don’t see kids often. They forget the rules.

There’s also the distraction-free zone. Medication prep happens in a quiet area, away from phones, alarms, and chatter. No multitasking. One task: get the right medicine to the right child, in the right dose, at the right time. This simple change has reduced preparation errors by 40% in participating hospitals.

What Parents Must Do at Home

Hospital protocols are great. But most pediatric medication errors happen at home. And that’s where parents have the most power to prevent harm.

Store medicine up and away. Not on the counter. Not in the purse. Not in the nightstand. Use a locked cabinet or a high shelf with a childproof lock. Even if you think your child can’t reach it, they probably can. The CDC says 75% of parents who thought their storage was "safe" were wrong.

Always relock child-resistant caps. Seriously. Every time. Even if you’re in a hurry. If the cap isn’t fully twisted, a child can open it in seconds. And don’t remove pills from their original bottles. That’s the #1 cause of accidental ingestions. A 2020 study found 45% of cases involved medicine taken from open containers.

Use the right tool. If the medicine comes with a syringe or dosing cup, use it. No spoons. No droppers without mL markings. If it doesn’t have mL on it, throw it away and ask for a new one.

Know the Poison Help number. Save 800-222-1222 in your phone. Write it on the fridge. Tell your babysitter. If you ever suspect your child swallowed something they shouldn’t, call immediately. Don’t wait for symptoms. Don’t Google it. Don’t panic-just call.

Never call medicine candy. Ever. Even if it’s sweet. Even if your child loves it. That’s how kids learn to seek out medicine. Instead, say: "This is medicine. It helps you feel better, but it’s not food."

How to Give Medicine Correctly

Even with the right dose and the right tool, giving medicine wrong can cause problems. Here’s how to do it right.

For liquids: Aim the syringe or cup toward the back of the mouth, against the cheek-not the tongue. That reduces choking and helps the child swallow naturally. Don’t pinch the nose or force it. That can cause gagging, vomiting, or aspiration.

For pills: If your child can’t swallow them whole, ask your pharmacist if it’s safe to crush them. Some pills are designed to release slowly. Crushing them can be dangerous. If it’s okay, mix the powder with a small amount of applesauce or yogurt-not a full cup. That way, you know they got the whole dose.

For patches and creams: Wash your hands before and after applying. Keep the patch covered. If it falls off, replace it with a new one. Don’t reapply the same one. And keep patches out of reach-kids have been known to peel them off and put them in their mouths.

What’s Changing in the Future

Progress is happening. The FDA now requires new pediatric drugs to come in standardized concentrations. That means if two companies make the same medicine for kids, they’ll use the same strength per mL. No more confusion between 10 mg/mL and 25 mg/mL. This could cut concentration-related errors by 60%.

More hospitals are using pictogram-based dosing sheets-simple pictures showing when and how much to give. Studies show these improve accuracy by 47% in families with low health literacy. That’s huge.

And now, the CDC and the American Academy of Pediatrics are pushing for "teach-back"-a simple technique where you ask the parent to repeat the instructions in their own words. If they can’t explain how to give the medicine correctly, you haven’t done your job. This reduces home errors by 35%.

But the biggest change isn’t technological. It’s cultural. Pediatric medication safety is no longer seen as a niche concern. It’s a core part of every healthcare interaction. And for parents, it’s no longer optional-it’s essential.

Final Reminder: One Mistake Can Change Everything

A single pill. A teaspoon too much. A bottle left on the counter. These aren’t minor oversights. They’re life-threatening. Children don’t have the body size, the metabolism, or the ability to tell you when something’s wrong. That means adults have to be perfect.

Don’t rely on memory. Don’t guess. Don’t assume. Use the tools. Follow the rules. Store it safely. Measure it precisely. And never, ever say it’s candy.

If you ever have even a tiny doubt about your child’s medicine-call your doctor. Call your pharmacist. Call Poison Control. Better safe than sorry. Because in pediatric medicine, there’s no second chance.

Can I give my child adult medicine if I cut the dose in half?

No. Adult medications are not designed for children, even in smaller amounts. The ingredients, fillers, and release mechanisms can be unsafe for a child’s developing body. Always use medicine specifically formulated for children, and only use it as directed by a doctor or pharmacist.

Is it safe to use old medicine for my child if it worked before?

No. Medicines expire. Their potency decreases over time, and chemical changes can occur. Even if it looks fine, using expired medicine can be ineffective or dangerous. Always check the expiration date and dispose of old medication properly. Many pharmacies offer take-back programs.

What should I do if my child swallows medicine they weren’t supposed to?

Call Poison Control immediately at 800-222-1222. Do not wait for symptoms. Do not try to make your child vomit. Have the medicine container ready when you call-this helps them identify the substance and give you accurate advice. If your child is unconscious, having trouble breathing, or having seizures, call 911 right away.

Why are liquid medications measured in milliliters instead of teaspoons?

Because teaspoons and tablespoons vary in size depending on the spoon used. A kitchen teaspoon can hold anywhere from 4 to 7 milliliters. That’s a huge range for a child’s dose. Milliliters are precise and standardized. Using mL-only dosing devices like oral syringes eliminates guesswork and prevents dangerous overdoses.

Are over-the-counter cough and cold medicines safe for toddlers?

No. The FDA and American Academy of Pediatrics strongly advise against using OTC cough and cold medicines in children under age 6. These products don’t work well in young kids and carry serious risks, including rapid heart rate, seizures, and even death. For cold symptoms, use saline drops, a humidifier, and plenty of fluids instead.

How can I teach my child about medicine safety without scaring them?

Keep it simple and positive. Say: "Medicine is for grown-ups to give, not for kids to touch." Use role-play: let them practice handing you a pretend medicine bottle and saying, "Can you help me take this?" Reinforce that medicine is a tool, not a treat. Avoid calling it candy or saying "it’s okay to try a little." Focus on safety, not fear.

Heidi Thomas

December 4, 2025 AT 11:22Alex Piddington

December 5, 2025 AT 06:37Yasmine Hajar

December 6, 2025 AT 06:41Jake Deeds

December 8, 2025 AT 04:47val kendra

December 10, 2025 AT 04:15George Graham

December 10, 2025 AT 12:12John Filby

December 10, 2025 AT 15:34Elizabeth Crutchfield

December 11, 2025 AT 08:06Ben Choy

December 12, 2025 AT 02:46Emmanuel Peter

December 14, 2025 AT 01:24Ashley Elliott

December 15, 2025 AT 17:48Chad Handy

December 16, 2025 AT 03:29Augusta Barlow

December 16, 2025 AT 14:03